After a Domestic Violence Arrest: Lessons to Learn from Nonviolent Communication

If you’ve been recently charged with domestic violence, your life could become quite complicated very quickly, especially if convicted. However, this time can also be a teaching moment—an opportunity to step back from this dark chapter and learn a more productive way of thinking and communicating.

The reasons why we humans sometimes turn to violence and aggression are too numerous and complex to explain here—nor are we qualified to delve into the psychology behind it. However, as the University of Michigan points out, domestic violence typically occurs as a repeating cycle, one that begins with a breakdown of communication. It naturally follows that if couples can create meaningful channels of communication, the cycle of domestic violence may be interrupted. The problem in many cases is that one or the other partner doesn’t understand the best ways to communicate—and the resulting frustration may erupt into aggression.

In the 1960s, an American psychologist named Marshall Rosenberg—himself a domestic violence victim from childhood—developed a process called Nonviolent Communication. The underlying theory behind this approach is that humans are innately compassionate, and violence is a learned behavior that develops from the inability to communicate needs effectively. Rosenberg utilized these principles quite effectively as a mediator to diffuse tensions between rioting college students and college administrators in the turbulent ’60s, as well as in peacemaking efforts during the desegregation process of the civil rights era. Since those days, many have utilized these principles to learn to communicate more compassionately and effectively.

The Basic Concepts of Nonviolent Communication

Nonviolent communication is sometimes also called “compassionate communication” because of its underlying concept that we are all compassionate by nature. According to the Center for Nonviolent Communication (CNVC) website, compassionate communication can be classified in four steps:

1. Making observations;

2. Expressing feelings;

3. Communicating needs; and

4. Making requests.

An example of this process might be as follows: If your domestic partner is saying or doing something that triggers your anger or causes you pain, rather than resorting to criticizing and/or yelling (which may lead to alienation and eventually violence), you might reframe the conversation in this way:

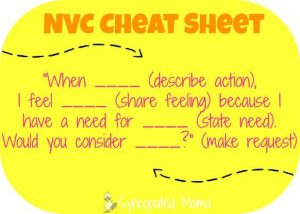

“When I see you do ______, (observation) I feel irritated (or hurt, or angry) because I need ______. Would you mind doing _____ instead? (request)”

This framework may seem foreign at first, but according to the underlying theories behind CVNC, this form of communication isn’t based on anything new—it’s what meaningful communication looks like in the absence of violent thoughts and feelings. Thus, it’s a model to be learned—or rather, in a sense, re-learned.

Learning to Communicate Feelings and Needs

One of the first steps in learning a better way of communicating is to know your own heart and soul—what you feel, what you need and what you want.

Expressing your feelings is one thing—having the vocabulary to express those feelings is another, especially considering so many of us have been conditioned to suppress our feelings. If you struggle to verbalize how you feel, this process may seem quite challenging, or even silly. However, if you have become violent toward your partner, it’s worth considering that the violence has actually emerged from those stifled or unexpressed emotions, and therefore learning to communicate those feelings calmly may be a way to disrupt the cycle of violence.

Feelings are typically expressed as adjectives. What do you feel when your needs are unmet? Do you feel hurt, agitated, disappointed or envious? What about when your needs are being met? Do you feel happy, satisfied, warm? Consider starting a journal just to make a running list of adjectives like these.

Another important facet of this self-discovery is to identify your needs—so make another list in your journal of what you believe your most basic needs are. Do you feel the need for freedom? For belonging? To be understood? The thrill of a challenge? A sense of purpose? Once you’ve identified these needs, you can begin associating feelings with those needs as they are met, or otherwise unmet.

Listening and Expressing

Communication is not a one-way street. It’s not one person transmitting information and the other person receiving that information. Communication runs in both directions. For that reason, the CNVC approach applies the four steps of observation, feelings, needs and requests in both directions: empathetically listening and honestly expressing. Your partner also has feelings and needs, and hers are just as valid and important as yours are. Thus, effective nonviolent communication involves learning to listen compassionately to the observations, feelings, needs and requests of the other person, then honestly sharing your own.

Domestic violence is a toxic, destructive cycle that can cause serious harm to people you care about as well as yourself—not to mention the legal and criminal complications of it. The best thing you can do for yourself and your family in the wake of a domestic violence arrest is to take concrete steps to break the cycle before it repeats—to make sure it doesn’t happen again. The concept of nonviolent communication can be a powerful tool to help disrupt this cycle and start you on the process of restoring your family to wholeness.

If you’re facing domestic violence charges and need compassionate legal representation, we are here to help. Call our offices to learn more.

Los Angeles Criminal Defense Attorney Blog

Los Angeles Criminal Defense Attorney Blog